Catching Fire came out November 2013.

Mockingjay: Part I came out November 2014.

In between, Mike Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, and the Ferguson Uprising took place.

This essay is about what it was like to live in an America that can rapturously and enthusiastically consume and cosplay revolution, and can look on real world resistance with disdain.

The first installment in the Hunger Games cinematic franchise was compelling, to be sure, but it was admittedly a bit underwhelming. For a story about a nation that punishes its citizens by dividing them into districts and then pitting their children against each other in a televised battle to the death, the first movie seemed to intentionally shy away from capturing the heinous nature of it all. It was dust-bowl bleary, certainly, but Katniss’ home in District 12 felt like stylized, not institutionalized, poverty. Once in the actual arena, it even felt a bit bright and breezy, portraying fellow competitors—you know, other children who were fighting to the death—as Katniss’ antagonists much of the time, and showing the Capitol—the seat of power responsible for all this—in short, visually captivating bursts, usually when Haymitch was soliciting donors to send Katniss gifts when she put on a good show.

Where the novel had been arresting, the first film went to great lengths to be another world, giving me pretty constant reprieves from the supposed oppressive injustice of Panem.

Catching Fire was the second novel in the Hunger Games trilogy, and it ground almost to a complete halt for me. Bluntly, Katniss performs a long, laborious, completely uncharacteristic wallowing act that felt very much like a middle book trying to rustle up enough story to justify the fact that there are three books. Because the hard part is apparently not being poor, oppressed, and living in a world where you’re too disconnected from your fellow countrypeople to effectively fight back. The hard part is having to say you’re in love with Peeta. She could not get into it, and I, in turn, could not get into that.

But the film adaptation. We bookish types like to bandy around mantras like “the book was better,” as though it’s a golden rule, like no film has ever improved on its source material. That’s just not true. I personally have several examples of movies that are better/more effective/more compelling than the novels that birthed them, and that’s not even speaking to adaptations that are simply as good. Catching Fire, the movie, reined in Katniss’s pity party and apparent willingness to jeopardize the family she went into the arena to save in the first place, and it made the games themselves feel real.

Importantly, it made the world in which the games could exist feel real. It was darker, and more violent… and to be honest, I was kind of amazed at how well received it was. It was, after all, about a revolution in the making. It was about a police state, in which there were no devil’s advocates arguing that there might be a few bad apples spoiling the bunch, or a few good guys mistakenly on the wrong side. There was an oppressive, dehumanizing, antagonizing, intensely penalizing power majority that was altogether wrong—and America celebrated it.

Three finger salutes went up all over the country.

Not only was it a hit, Catching Fire was praised for disallowing the viewer any distance from the violence. The District 11 execution that marks the first bloodshed in the film is heralded for being the focus of a steady frame—as opposed to the shaky cam employed in the first movie—and for being a moment during which Katniss was, as one review mentioned, “made to fully realize the capability for cruelty inherent in the government of Panem.” Yes, a set of doors closed before the bullet left the chamber—it’s PG-13, friends—but the effect was palpable. The viewer was spared neither that this was a full-scale terror, nor the immutable truth of the wrongness of military brutality being used against civilians.

That execution of the elderly Black man in that scene is meant to be impactful, but it knocked the wind out of me. It reminded me that in the real world, in real life, in my country, we have been terrorized by the repeated slaying of Black men, women, and children, at the hands of law enforcement. That in the film he was pulled from a crowd and made to kneel before being shot in the head did not feel fictionalized enough. It did not feel extreme or hyperbolic when as a child I’d seen footage of four cops beating a man until he was disfigured and required mobility aids. A country that could see that, acquit the perpetrators, and then demonize the community’s response, was telling you that time does not heal institutional and intentional wounds. It might infantilize you with admonishments to leave the past behind, but there is a straight line between chattel slavery and Jim Crow and refusal of civil liberties and lynchings and overcriminalization and economic disenfranchisement and cultural erasure and sustained gaslighting and mocking the very concept of reparations. And so while someone divorced from the reality of incessant oppression can split hairs and argue semantics, for me, there was nothing sensational about that execution. That my country could be riveted by Catching Fire’s unapologetic centering of such a killing—provoked in the film by a whistle and a salute of solidarity that tacitly defied the Capitol, and carried out in front of his own community, as District 11 was apparently the Black district—filled me with a wonderment, and a kind of cautious energy.

The optics hadn’t been accidental.

The themes couldn’t be overlooked.

Surely, all across the country, my real country, a realization was—forgive me—catching fire. Surely.

Fast-forward to August 2014, and the killing of Mike Brown. The first wave of the Ferguson Uprising, a series of riots that took place in Ferguson, Missouri over the course of the next five months, began the next day. It had been nine months since Catching Fire came out, but as the second film in a series, its popularity had persisted, as had its publicity. Surely, that same overflow of support and recognition was going to rise up, I thought. Surely people were going to raise their hands in solidarity, and disallow history to repeat itself. It wasn’t going to be mostly Black Americans decrying this most recent slaying by a police officer. Surely the public wasn’t going to stand for the victim blaming and character assassinations it had permitted in the past.

Then the nation’s most celebrated newspapers informed me that Mike Brown, the teenage victim, was no angel.

Then the media and various personalities denounced the community’s response, and the anger, and the riot.

Whatever hope I’d nursed in those first awful hours bled out. Whatever I knew and believed about the socializing agent of entertainment media, and the fact that messaging is of paramount importance in either perpetuating the status quo or laying a foundation for re-education and enculturation—it hadn’t happened. If it takes exposure to get to awareness to get to empathy to get to solidarity to get to action, America’s progress was always slower than I wanted to believe.

By the second wave of the Ferguson Uprising, spurred by a grand jury declining to indict the officer responsible for Mike Brown’s death, it was November, and Mockingjay Part 1 was in theatres. Katniss Everdeen bellowed, “If we burn, you burn with us,”— but outside the dark theater, the world did not come to Ferguson’s aid. The country did not rally to stand against the militarization of the police force, or the separate set of laws under which officers had proven to operate. Those who came did so to document, to photograph, to disseminate, and then to talk about it somewhere far away, from a distance that allowed “civil discourse” to seem like a solution. And while it would be unfair to say that Ferguson wasn’t a “come to Jesus” moment for anyone, nothing swept the nation but viral images of alternately defiant and devastated protesters, of disproportionately equipped police officers and National Guard service people.

America, it turned out, was less concerned with the death and terrorization of its citizens even than Panem. Revolution was a high concept, meant for splashy acquisition deals that would become blockbuster YA novels and then glittering film adaptations. It was to be consumed, not condoned.

How very Capitol of us.

Recently the long-awaited prequel to the Hunger Games trilogy was finally teased, and it turned out that the protagonist at the center will be a young Coriolanus Snow. As in future president and villainous oppressor of Panem, Coriolanus Snow. And seeing as the author lives in the same America that I do, you know what? That tracks.

It’ll make one hell of a movie.

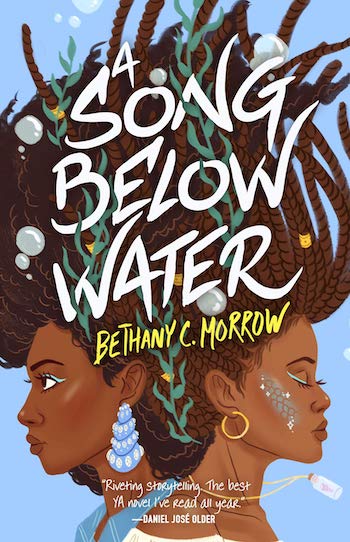

Bethany is a recovering expat splitting her time between Montreal, Quebec, and upstate New York—yet another foreign place. A California native, Bethany graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a BA in Sociology (but took notable detours in the Film and Theatre departments). Following undergrad, she studied Clinical Psychological Research at the University of Wales, Bangor, in Great Britain before returning to North America to focus on her literary work. Her YA novel A Song Below Water publishes in June 2020 with Tor Teen.

Bethany is a recovering expat splitting her time between Montreal, Quebec, and upstate New York—yet another foreign place. A California native, Bethany graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a BA in Sociology (but took notable detours in the Film and Theatre departments). Following undergrad, she studied Clinical Psychological Research at the University of Wales, Bangor, in Great Britain before returning to North America to focus on her literary work. Her YA novel A Song Below Water publishes in June 2020 with Tor Teen.